Introduction (500 words)

Tarkovski - called cinema “the art of sculpting in time”

“The motion picture can be thought of as a program. And it is more precisely a program than either a language or a mere set of stimuli. It is a very complex set of instructions utilising images, actions and sounds, a string of commands to attend to this now, in this light, from this angle, at this distance, and so forth”

“To recall earlier sequences and anticipate future ones” (p.12)

A brief history of sound and image in cinema (500 words)

Early opinions of the purpose of film

Andre Bazin - “For Bazin, the film was neither a product of the mind nor a clash of concepts, but rather a photochemical record of reality.” (p.5) - film was not considered an art form.

“An apparent advantage to writing film from this perspective is that film writers may feel free to appropriate the language of psychoanalysis, Marxism, or any pop culture movement or special interest cause, without assuming responsibility for their theoretical imperatives. Such writers may claim adherence to no theory at all.”

Started with political undertones - film was a method of propaganda, promotion of an ulterior motive without consequence

“By the mid eighties, a few courageous film theorists suggested that cognitive science might be a more productive path than the then pervasive, psychoanalytic/Marxist approach to film study.” (p.8)

Multi modal connections (500 words)

the human brain is primarily an image processor. - arguable

Studying those with inhibited senses is an effective way of acknowledging the complex interplay between sight and vision

“Deaf people raised on sign language apparently develop a special ability to read and structure rapid visual phenomena”...”raises the question whether the deaf mobilize the same regions at the centre of the brain as hearing people do for sound - one of the many phenomena that lead us to question received wisdom about distinctions between the categories of sound and image”

(page 12)

Within film “The viewer can be thought of as a standard biological audio/video processor”(page 13) processes the amalgamation of media as one. The ease at which we do this depends on the filmmakers intentions and how meticulously they blend the multi modal

Sound more than image has the ability to saturate and short-circuit our perception (page 33)

since early 2007, the Internet has seen a 9900 percent increase in the use of visualized information

‘visuals are more concrete to the brain than words, they’re easier to remember, as well.’

‘The visceral, emotional reactions that strong visuals can evoke are even quicker for our brains to process than emotion-neutral visuals — 13 milliseconds on average. Responding to sound is only slightly slower, at 146 milliseconds on average’

the tasks involved in processing and enjoying music are distributed across several brain areas.”

one study asked students to remember many groups of three words each, such as dog, bike, and street. Students who tried to remember the words by repeating them over and over again did poorly on recall. In comparison, students who made the effort to make visual associations with the three words, such as imagining a dog riding a bike down the street, had significantly better recall.

visual information—including the performer's sex, attractiveness, movement, and so on— could confound listeners' ability to make judgments of the quality of the music being performed.

“We persist in ignoring how the soundtrack has modified perception”

“Each perception remains nicely in it’s own compartment” - as an audience, we never consider the interplay between the senses as sound and image are usually combined seamlessly

“Identifying so called redundancy between the two domains and debating interrelations between forces”...”Which is more important, sound or image?”

The image projects onto them meaning they do not have at all by themselves

Sound more than image has the ability to saturate and short-circuit our perception (page 33)

Application to film and music (1000 words)

electronic music performances are often sensor or laptop-based, which are not always visible to the public and whose usage does not require big gestures and actions from the performer.

Any musician that reaches audiences of a certain size will eventually face the question of A/V accompaniment, regardless of whether visual presentation has been central to their work or not.

an unclear cognitive link between the sound and the performer’s actions

The visuals are what the viewer tends to mostly focus on and the sound subconsciously alters how the visuals are perceived.”

Commentary on Bergman’s Persona - cutting sound from one scene sees a succession of 3 shots - “the entire sequence has lost its rhythm and unity”

“Sounds we didn’t especially hear when there was only sound emerge from the image like dialogue balloons in comics.”

(page 4)

“Audiovisual Illusion”

“Informative value with which a sound enriches a given image so as to create a definite impression”

Added value - Bergman “(eminently incorrect) impression that sound is unnecessary, that sound merely duplicates a meaning which in reality it brings about”

Image synchronism - (sounds happening in time on screen, blows, explosions etc.)

(page 5)

“Voice that is isolated in the sound mix like a solo instrument”...”sounds (music and noise) are merely an accompaniment.)

“You will first seek the meaning of the words, moving on to interpret the other sounds only when your interest in meaning has been satisfied”

(page 7)

“Music can directly express its participation in the feeling of a scene, by taking on the scene’s rhythm, tone, and phrasing”

“On the other hand, music can also exhibit conspicuous indifference to the situation, by progressing in a steady, undaunted, and ineluctable manner”

(page 8)

Electronic - Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers (1000 words)

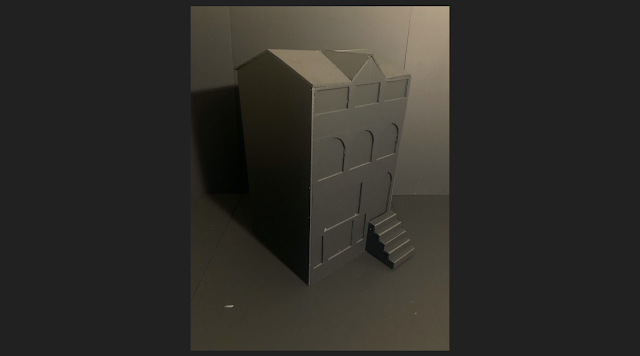

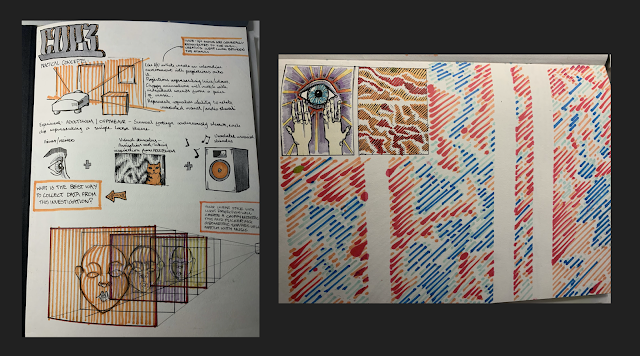

Practical (1000 words)

I love to have the visuals connected to the music, synchronized and tight. In the best case, it should represent the sound on the visual level.

While it isn’t subtle, spectacle is effective, stunning an audience’s senses and leaving a big impression. Often, video isn’t even necessary, as lights, especially strobes, can accomplish this on their own. And as lights get more technologically advanced, it becomes easier to do interesting things with them.

How clear is the relationship between the performer’s actions and, in our particular case, the audiovisual result?”.

“Sound superimposed onto image is capable of directing our attention to a particular visual trajectory.”

(page 11

Conclusion (500 words)